Solidarity Power: Strikes Gain Momentum as Leaders Fail Us

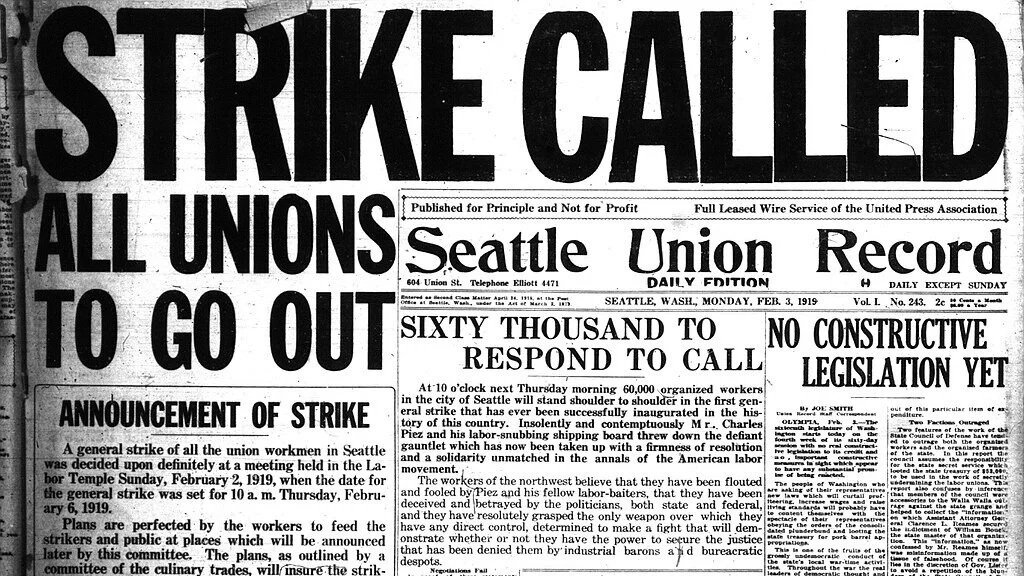

“Strike Called” headline on Seattle Daily Record, 1919

Blackouts and strikes. Boycotts and shutdowns. Even as our fascist government relentlessly commits atrocity after atrocity and our prospects for dignity and safety evaporate, our resistance continues unabated.

Over the past decade, the means of resistance and the analysis and knowledge behind it has visibly shifted. Instead of posting a black box on social media to project discontent, US-ians have learned to hit their targets where it hurts—in their wallets. We are riding the tailwinds of 2023’s Hot Labor Summer, advancing in the momentum of the BDS movement, and recalling the effectiveness of the Tesla Takedown. We are witnessing the rebirth of a generalized United States labor movement.

In response to ICE’s especially visible extrajudicial violence in Minneapolis (not to mention the violence on AAPI/BIPOC hidden away in detention centers), and as an escalation of the city-wide strike on January 23, organizations—notably, BIPOC student unions at the University of Minnesota—are calling for a nationwide general strike. Seattleites are answering the call, whether they’re closing their businesses or workers withholding labor for the day. While the widespread solidarity, anti-ICE posters, and the determination to strike warms the heart, these single-day strikes reveal that our labor movement at large still has much to learn.

To put it into perspective: In November, I covered Starbucks Workers United Strike. It is almost February, and workers are still on strike. They have not worked or received wages for two months. For many who live paycheck-to-paycheck, two months of lost wages translate to an empty fridge and eviction. Workers are able to sustain their strike due to the structural support provided by a union: strong and clear messaging relayed by a public relations team, an already existing system of nationwide coordination, and, crucially, a strike fund to keep their workers above water.

A national pause to business as usual is encouraging, but to billionaire corporations, indifferent millionaire politicians, and a federal administration hellbent on fascist absurdity, a single-day pause is not enough. On the other hand, for many workers and small businesses, a single-day pause is already too much. The masses are demonstrating their willingness and their quantitative power; the next step is to build the infrastructure for longevity and qualitative power. To effectively wield the weapon of the strike, we must learn its histories, mechanisms, and its place within the overall scope of resistance.

Just a little history:

“It is in truth no trifle for a workingman…to ensure hunger and wretchedness for months together, and to stand firm and unshaken through it all. ...People who endure so much to bend one single bourgeois will be able to break the power of the whole bourgeoisie.” — Friederich Engels, Condition of the Working Class in England in 1884.

-

The bourgeoisie reversed these advances with their extremely effective strategy of divide and conquer—this time in particular, by creating and exacerbating gendered antagonisms.

Withholding labor, historically, one of the strongest means of resistance of the working class. In fact, the practice predates capitalism; records show that discontented peasants withheld their labor when their lords summoned them to work on their fields. Silvia Frederici, a leading feminist Marxist, wrote that rent and labor strikes continued throughout the feudal and mercantile era, with its effects reaching a head after the Black Plague wiped out a majority of the workforce and increased the value of labor. In her book Caliban and the Witch, which (in part) discusses the transition from feudalism to capitalism, she writes, “...the rebels did not content themselves with demanding some restrictions to feudal rule, nor did they only bargain for better living conditions. Their aim was to put an end to the power of the lords. As English peasants declared in the Peasant Rising of 1381, ‘the old law must be abolished.’” The strikes coalesced into mass rebellion. Workers had every holiday off, were provided meals by the employer, and were even paid for their commute to work!

Peasants at work

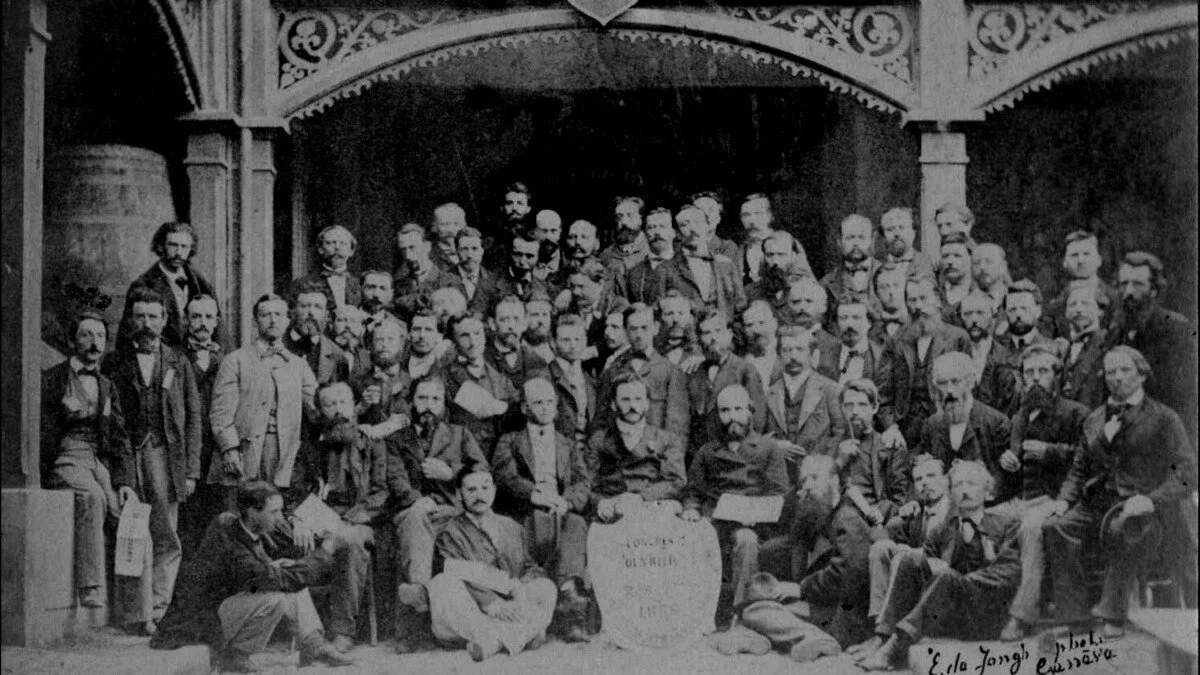

Marx and Engels deemed strikes an integral part of “social war” or “class war.” Marx’s work with the International Workingmen’s Association highlighted the importance of solidarity and funding to strike effectiveness. He once wrote triumphantly: “Our International celebrated a great victory. We secured monetary aid for the striking bronze workers of Paris from the British trade unions. As soon as the bosses saw this they gave in.”

Like the peasants in 1381, Marx emphasized that strikes were just one part of a series of means to an end. Strikes themselves do not a revolution make. In his pamphlet, Value, Price, and Profit, Marx wrote: “[The working class] ought not to forget that they are fighting with effects, but not with the causes of those effects; that they are retarding the downward movement, but not changing its direction; that they are applying palliatives, not curing the malady. Instead of the conservative motto, ‘A fair day’s wages for a fair day’s work!’ they ought to inscribe on their banner the revolutionary watchword, “‘Abolition of the wages system!’”

In other words, strikes operate within the framework of capitalism. A strike alone may win a favorable contract for workers, but will not revolutionize the system. By no means am I dismissing the power of the strike; I am instead insisting that we do not over or under-play its role in an anti-capitalist movement. In The Communist Manifesto, Marx and Engels argued that strikes build the power and unity of the working class to eventually build the infrastructure for a revolution.

I offer a more contemporary and prescient example: After the Delano Grape Strikes and Boycotts from 1965 to 1970, farmers won an impressive contract that included a wage raise from $1.10 an hour to $1.80 with incremental increases over the next few years, secured more money towards health and welfare benefits, and created stricter regulations on the use of pesticides. The United Farm Workers, an alliance of Mexicans and Filipinos helmed by labor leaders like César Chávez, Larry Itliong, and Dolores Huerta, used a multi-pronged approach to achieve these goals.

Across years of determined and disciplined struggle, the UFW established alliances with other unions to secure funding, print posters and pamphlets, hold joint rallies and marches, encouraged consumers to boycott non-union corporations, and even utilized connections with the Catholic clergy to put pressure on their targets. This impressive, robust network allowed the workers to commit wholeheartedly to their cause.

As you can see, if we do not have the infrastructure for a strike, we cannot even dream of building an infrastructure for a working class revolution.

International Workmen’s Association at Geneva, 1866

In regards to the current situation with ICE (which Jacobin wisely connects to the working class struggle), Minneapolis is a shining example of building said infrastructure. Neighbors are buying groceries and helping with costs of living for those forced to shelter in place; a local staple, Modern Times Cafe, switched to a completely free and volunteer-based structure; Signal chats buzz with a robust exchange of information and requests for mutual aid. Minneapolis has a harrowing history with state-sanctioned murder, and its residents are responding accordingly.

-

The collective spirit of the 1919 General Strike lives on. The Seattle Union Record inspired the founders to create The Evergreen Echo, a worker-owned publication.

Before Minneapolis’ recent general strike, Seattle carried out the United States’ first and largest general strike in 1919. It was an admirable feat: the entire city shut down, but people remained fed, housed, and warm. The strike lasted for four days (can we stretch one day into four?). Unfortunately, the strike itself did not bear desirable results—as in the call for increased wages for shipbuilders—with internal discord and looming military occupation as the primary reasons for its failure and subsequent quashing of the working class movement in the Pacific Northwest.

As present-day Seattle prepares for its own siege, and as Seattleites demonstrate their determination by withholding labor, we must build similar networks of support. A one-day general strike pales in comparison to days, weeks, or months without wages. The mistakes of a century ago still haunt us. We must ask: How will we feed and house ourselves? What are our goals? What are our clear calls and demands? Is the strike centralized through union representatives or labor organizations? How can non-unionized workers strike without union protections? How do we respond to outright military occupation? Where do we even begin?

I am still answering those questions, weighing them against my own personal conditions as a non-unionized barista working hand-to-mouth. I live and work alongside others who demonstrate willingness, but have different needs and circumstances that preface any risky action. The little things here and there give me hope and direction, like the frankness of my coworkers and peers as we discuss preparations and the building of neighborly coalitions.

I do not believe that we live in “unprecedented times”; though the particulars may change, history demonstrates that the ruling class and the masses at large have and will clash again and again. While it is unlikely that a single-day strike alone will abolish ICE and the DHS (yes, abolish both!), I find encouragement in the increasing regularity and vigor of each call for a general strike. When shit gets worse, we fight back harder.

Should efforts for preparation fail and the bombs start to fall tomorrow, as they already have in Minneapolis, the flames of necessity will fuel the fire within all of us.